Redefining spaces

Part One: "You Don't Know The Whole Thing (2019)"

In 2019, I made the first of what I call temporary drawing-based installations. At first, this part of my art making seemed to come as an opportunity out of the blue, but really it was years in the making. Looking back, I can trace a pretty distinct line back to the genesis of this idea with more clarity than before. I’ll have to work on that part for another time. This, however, is the first of a three part series looking at the development of these installations over the past five years and the threads that carry through each one.

Sometime in the spring of 2019, I received an email from a friend of mine who worked at a German designer kitchen showroom called Poggenpohl that has since closed their Philly location. He said that someone had bought one of the demonstration kitchens, he had a big open space for several months coming and would I be interested in hanging artwork there. He’d been having small art shows in the showroom for a while. In fact, I had already shown some small paintings there the year before. I was intrigued, but didn’t want to just hang more paintings. The space that was available was about 8 x 13 feet x 12 inches, which made for an interesting challenge because of the set-back.

I’d been thinking of an idea for a drawing-based wall installation for a while. It originated with the question of how to engage with drawing that stretched the meaning of what a drawing could be and what that could possibly look like. I wanted this work to function in an ambiguous space between drawing and sculpture. At that point, I had actively incorporated the glyphs into my work and was deep into using them along with other repetitive mark-making and stenciling to explore a particular energy and sense of overwhelm that living in an urban environment can have. I wanted to make something that was a drawing, but one that engaged with that space in a more sculptural way. There needed to be a lot of transparency, overlapping and obscuring of elements, much like what happens in my paintings.

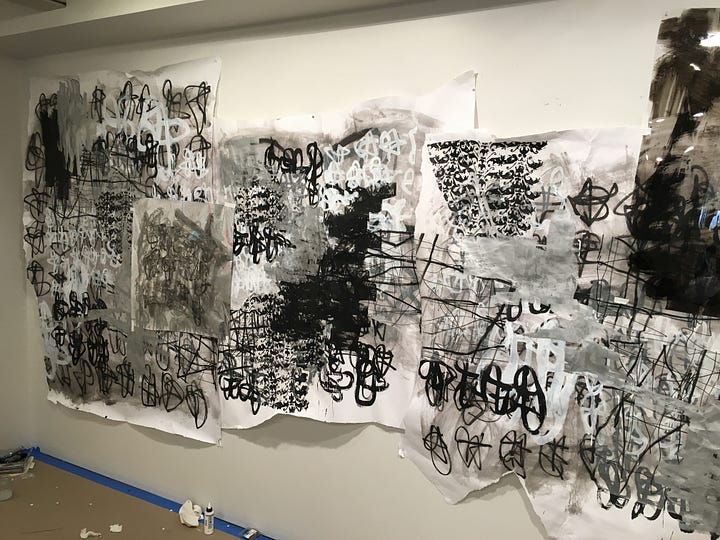

Other things that were in play included not making a pre-set plan for how the installation was going to look. I made no sketches, only looked at the space before making any of the drawings. I had a sense of how big the area was and what I needed to do to fill it, which meant starting off with some large drawings to fill up the first layer on the wall and go from there. The drawings were made with a combination of acrylic paint and acrylic markers. I also did different things to change the surfaces of the more pristine looking materials, like the clear acetate and silver mylar. I needed the piece to feel lived in; that it had had a life before entering this space.

To prepare, I had to make a lot of drawings on various materials in the studio, which included paper, frosted mylar, clear acetate, silver mylar and drafting paper. I tried to make sure that I made more than I was hoping to use, but nothing is certain until you get in the space ready to install. That’s where I figured out that I needed to make more work in-situ in order have this piece really take over the wall. Lucky for me, I wasn’t too far from the nearest art supply store, which was also my job at the time.

Not having a plan was also similar to how I paint, but the stakes here were a little higher in that there were a lot of (actual) moving parts. If something didn’t work, I would have to unpin, remove nails and tape to rearrange things, honestly a small sacrifice to make something like this work. I began with hanging the largest drawings on paper and built up and out from there. I used push pins, small nails and tape to hold everything together because I wanted a sense of fragility up close, while at a distance, it may seem to be more substantial in it’s presence.

I didn’t think about this at the time, but an unexpected layer to making this piece was the location and it’s function. This was a showroom for precision-made luxury goods that probably populated the kitchens of many of the condos in Old City, Philadelphia and beyond. I haven’t thought about it much, but I did wonder at the time what some of their clients may have thought of this installation that was anything but pristine in how it looked. I liked the idea of bringing a bit of what looked like chaos into a well-organized space. As thrown together as it may have looked, there was a lot of thought put into it coming together as I worked.

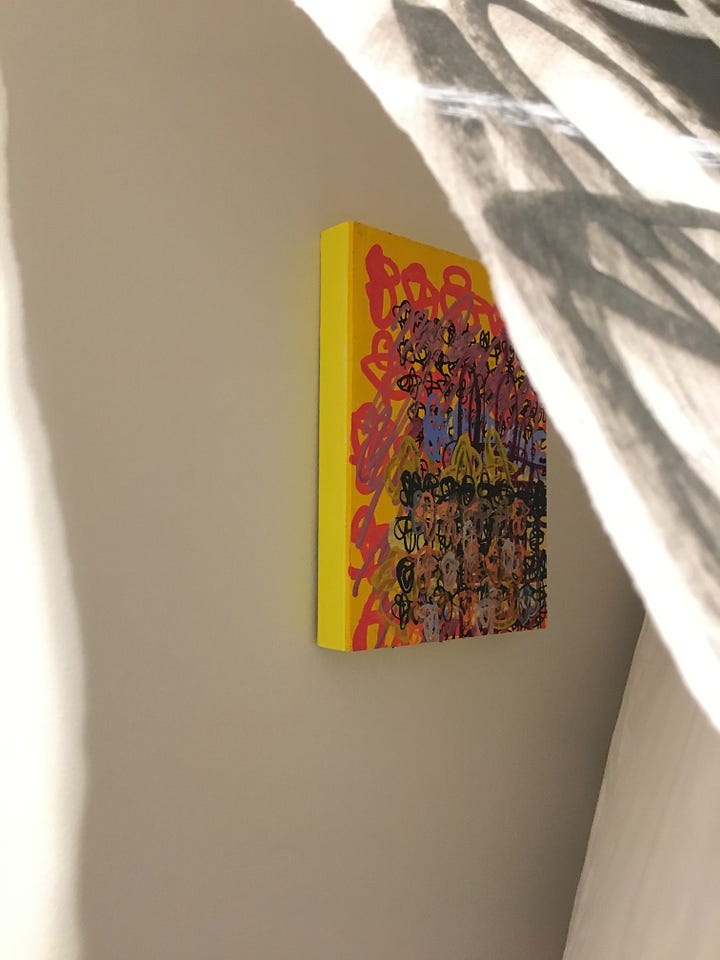

The work always comes first, titles last. It’s almost always been that way for me and You Don’t Know the Whole Thing was no exception. How the title came about was interesting, though. I was nearly done and realized that there was a bit of flatness to the piece on the left side. I remedied this by unpinning one side of one of the large drawings on the first layer and let it slide down a little. This created a small “cave” that was potentially noticeable enough that I found it distracting because there was no visual payoff when someone would look there. I had to think about it for a bit and the solution hit so hard, I let out an audible “YES!” and left for the day. I returned the next morning with a small painting that I’d made the night before and installed it behind the drawing, hidden from view except for that one side. That’s where You Don’t Know the Whole Thing got its title.

Digging deeper, I saw connections with how we go about everyday life not really knowing every possible angle of a story nor everything about the people in our lives. We experience others through the lens of specific relationships, places and times in our lives. We’re all multiple things to multiple people and can be: parents, siblings, children teachers, bosses, friends, lovers, etc… to a variety of others. Even within ourselves there dwell multiple beings and contradictions that make up the whole of who we are. This is what brought me to the title of this piece. That painting was placed there for visitors to find or not, but it definitely was the thing that pulled everything about YDKTWT into place.