The hardest part…

…is done. This past Monday, I finally got to deliver my work to the Bridgette Mayer Gallery with the help of my buddy, Brad Carney. Big thanks to Mark, the gallery preparator, who helped with carrying work from the truck to the gallery, as well. Things went pretty smoothly, except we had to park a half block away from the gallery because of it’s location on Walnut Street and the stringent parking situation in center city. Thankfully, we had a good day weather-wise with no rain and low wind. Had it been more windy than it was, we would have had to contend with having to wrestle with most of these pieces as sails. I’ve had to deal with that a couple of times in my life and it’s one of the worst things to have to contend with.

I have to say that it took the better part of the day afterwards for me to start feeling a bit relaxed. All of the stored tension in my body slowly began to diminish as I settled into knowing that the hardest part of this exhibition preparation was over with. It’s been months of making sure that I worked as hard as I could to get the works to a state where I could consider them finished. It takes a while for me to unwind enough to enjoy being at this place.

There’s no moss gathering, though. After wrapping the paintings last week, I was anticipating being able to start working on new ideas based on some of the new work I’m showing. Yesterday, I picked up some small hot press watercolor paper (9 x 12 inches) and made a bunch of new studies for possible new large paintings to come. I’m due to have a solo show at Mercer County Community College in October, so it’s a good time to generate new ideas. I’m looking forward to seeing what comes next with this work.

Since the tide has shifted in the studio with the show work being out of here, I’ve turned my attention to maintenance and upkeep. Yesterday, I took to photographing twenty works on paper made between late 2022 and into 2023. There’s about 43 more to do that are from 2023-24. I would have worked on those today, but I had a studio visit to prep for this afternoon, so I’ll get to the rest another day soon. I just finished uploading ten from the first batch to my website in the Works on Paper folder. I took a bunch of older glyph-related pieces off to make room for this new batch. I’m getting everything set up so that my work from the past couple of years are highlighted and the site is freshened up a bit.

I’m trying to get into the habit of reevaluating what I have on the site every four to six months or so to keep things updated. I look it over all of the time, but doing a deeper dive into what’s represented there and how it’s representing my work is always a good thing.

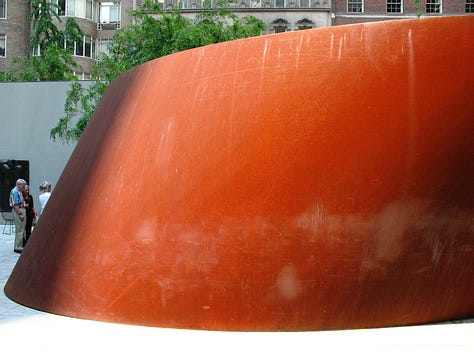

Richard Serra 1938-2024

Richard Serra was one of my long-time favorite artists. I first discovered his work by accident when I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art back in the early 90’s. At least I think it was the Met, it’s been a while. Anyway, I was really taken by what I saw, which were some of the early pieces like Strike and Delineator. They completely blew me away at the time. The way that my body and mind felt while engaging with this work left me with a lot to think about. With Strike, the first thing was the material itself being situated the way it was; a ton(s) heavy sheet of Cor-Ten steel protruding into the room from a corner with nothing seeming to hold it up except the fact that it was jammed into the corner. It bisected the room, so you almost had no choice but to engage with it. It asserted itself and dared you to blink.

Delineator was even more intimidating because of the one sheet of steel seemingly embedded in the ceiling above the viewer, while one is standing or walking on top of another, perpendicularly situated sheet on the floor. The sensations generated by being in that space still haunt me to this day, in the best way possible.

Around this time, I was heading back to school after having dropped out for five years. As I always tell people, I wanted my degree and the only thing I felt like working at was art. The previous five years and prior, going back to high school, I was steeped in realism and focused on still life and landscape painting. By the start of the 90s, things were shifting for me; I was no longer finding whatever it was in representational art interesting any more. I was becoming increasingly enamored with the worlds and spaces between things, actions and maybe even thoughts. The span of time and space between here and there that can stretch for centuries or nanoseconds at once. I no longer related well to depicting what I saw in front of me, I was after something beyond and wasn’t sure what exactly it was I was after, but encountering Serra’s work left a mark and a passage towards something I knew I had to explore.

I remember vividly going into Paley Library on Temple University’s main campus after being directed by one of my painting instructors to seek out the art section. This is where I had my second most memorable encounter with Serra’s work. I found these black bound books of his work with text in German, and possibly English, too, but I was most struck by how the work was presented in photographs: all black and white. No color images at all. I don’t know how many times I checked those books out from the library, but every chance I got I was looking through them.

The funny thing is, I had no inkling about becoming a sculptor. I was purely interested in Serra’s unwavering commitment to his ideals about how sculpture at scale can affect how we experience it, as well as his choice of materials to accomplish this with-steel. A rather unglamorous, rusting industrial material compared to more traditional materials like bronze. More than that, his perseverance in his unique visions about abstraction. That’s what I think stuck with me the most as a younger artist, that he remained absolutely committed to his artistic inquiries and singular focus. That’s one of the things that influenced me early on with my own work, having the courage to continue with what I’m doing regardless of what’s trendy or popular.

The following is a blog post of mine from October 28th, 2007 that was written after I attended a talk by Richard Serra at the University of Pennsylvania.

Richard Serra at Penn

Pardon the blurry shot but that's all I could get without using the flash on my camera during the talk with Serra and curator, Lynne Cooke last Thursday evening at the University of Pennsylvania. Cook co-curated Richard Serra Sculpture: Fourty Years.

The talk lasted for about an hour and-a-half, with Serra doing most of the talking and Cooke not really asking great questions. The thing about Serra that's impressive is how direct and engaging he is with his language as he is with his work. I really wish Cooke was a bit more engaging with her questions. For the most part, familiar ground was covered in terms of his development as an artist living and working in New York and Europe in the late 60's-early 70's. It was enlightening to find out that Leo Castelli bankrolled Serra's work for three years, even when Serra didn't sell anything. One of those stories that the stuff of myths are made of. I doubt there are many art dealers in the world who are willing to give young artists that kind of support any more.

It was interesting to find out that Serra had a part in the design of the renovation of MoMA. In order to accommodate the three newest sculptures in the retrospective exhibition, which closed in September, a portion of an outside wall had to be made into a door thorough which the plates that made up the works were brought into the museum on the second floor. Serra was asked how big the door needed to be. According to Serra, he said, "About 40 feet wide and 13 feet high" and so it was done. That's a lot of pull.

The question-and-answer session was a bit of fun. One guy asked Serra if the size of a lot of his work was related to his relatively small physical stature and a possible 'Napoleon complex', which Serra denied. Another question came from a student who asked what qualifications would Serra look for in a possible apprentice. The answer to this intrigued me since I've wondered how he managed to keep all of his projects going and how many people might be helping him. Serra said that he only has four people in his circle. Including himself, his wife, an office manager and another assistant.

Someone else had a comment about how the controversy surrounding Tilted Arc may have affected Serra's other work at the time; if Serra saw this as a "low point" from which his newer, "more refined" work came out of. Serra debunked this notion quickly by saying that he never stopped working during that time and that Tilted Arc was probably the "most refined piece" he's ever made.

With that, it was all over.

It is your commitment to your art that is the hardest part, and keeping those commercial voices at bay! It’s always helpful to see others staying with their work, no matter what. 🙌🏾🖤👏🏾 Thanks for sharing this. 🙏🏾